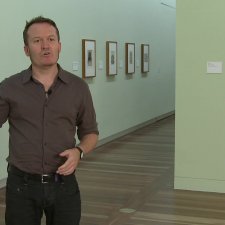

A decade ago as a curator at the National Gallery of Australia researching Australian surrealist art of the 1930s and 1940s, I was fascinated by the expressionist portraits created by Australian artist Albert Tucker In 2008 when I joined the team at the National Portrait Gallery, Tucker’s portraits gained a new relevancy for me and the concept for the exhibition Inner Worlds: Portraits & Psychology was born.

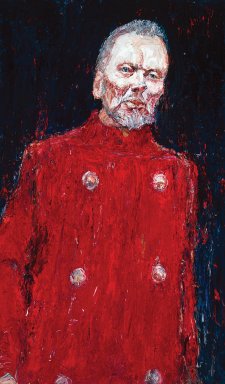

Tucker’s portraits of soldiers who have suffered psychological trauma are at the core of the exhibition Inner Worlds. They represent a young artist’s interpretation of the psychological impact of war and were a crucial step in the development of Tucker’s personal artistic vision. Throughout his life Tucker maintained a strong interest in psychology – the relationship between behaviour and mental processes. At the age of eighty, after a lifetime working as an artist, Tucker reflected upon the significance of the mind for creative processes, ‘I always listen to that’, he said, ‘that silence, that inner voice; and wait for what image comes up’. In an article about the work of a group of groundbreaking Australian modern artists published in Art in Australia in November 1940, artist and writer James Gleeson evoked the power of deeper levels of the mind when he described Tucker’s painting as ‘an indication of the clamorous incognito of the personal unconscious’.

In 1946 Albert Tucker made a claim for the supreme artistic value of primal creative expression in his essay ‘Exit Modernism’ written for the progressive intellectual publication Angry Penguins Broadsheet. Tucker drew upon Austrian-born educational psychologist Viktor Lowenfeld’s theories of visual and haptic perception as described in his book The Nature of Creative Activity (first published in 1936 and translated from German into English in 1939). For the visual type of artist, inspiration is drawn from the visible external world. For the haptic type, Tucker wrote, paraphrasing Lowenfeld, ‘inner bodily processes; muscular innervations, tactile memory, deep sensibilities, emotions and unconscious mental processes’ are primary. Lowenfeld had fled Europe via England to the USA in 1938. His discovery of what he termed haptic perception was made while teaching art to blind students in the 1920s. The evocation of inner processes through haptic perception had ethical implications for Lowenfeld; it led to social integration and personal independence. Lowenfeld’s book included examples of expressionistic portraits by haptic types that Tucker reproduced with his essay. Looking back at the influence of Lowenfeld’s book for him in an interview in 1982 Tucker recalled how the portraits affected him, ‘they were extraordinary’. For Tucker the raw and expressionistic style of the portraits by Lowenfeld’s haptic types resonated with those created by naïve and untrained artists. For Tucker these artists whose creative work was unaffected by the stylistic dictates of the day, and who drew primarily upon their unique ways of viewing the world, were the true ‘natural’ artists. Their work exemplified a freedom of vision and direct expression of the subconscious that aligned with the ideas of Surrealism and Expressionism, a view shared by Tucker’s fellow artists Sidney Nolan and Joy Hester.

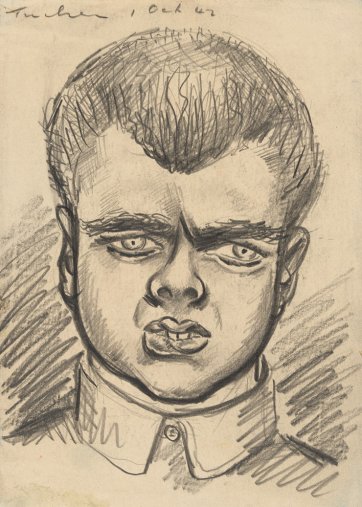

The psychologist Reginald Spencer Ellery, a member of the intellectual circle of John and Sunday Reed, had supported Tucker’s claim that he was unfit for army life, but in April 1942 Tucker was called upon for duty. After five months at the Wangaratta training camp he was transferred to Heidelberg Military Hospital. At Wangaratta Tucker was given a job re-drawing medical illustrations from books at a larger scale for a commanding officer’s lectures. The living conditions were tough in barracks in the town’s showgrounds where cold and wet seeped into the converted animal pens. At Heidelberg Military Hospital Tucker’s role was as a medical artist recording injuries of soldiers in the plastic surgery unit. It was here that he experienced at first hand the psychological effects of war on soldiers who had been severely traumatised by ‘battle fatigue’, the ‘bomb happies’ that inspired Tucker’s powerful portraits of traumatised soldiers.

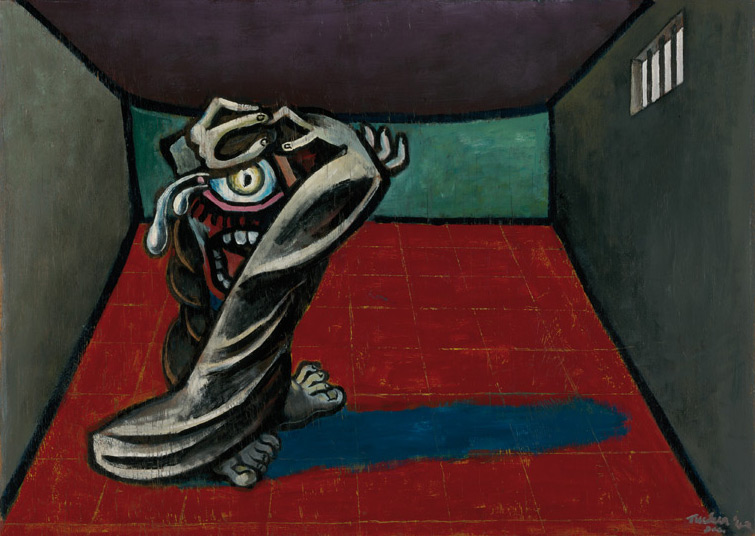

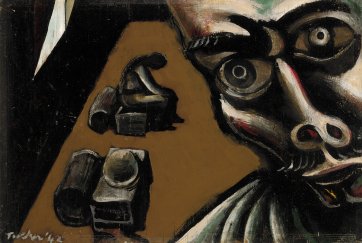

Tucker’s paintings of army life at the Wangaratta barracks describe claustrophobic scenes within compressed space, sometimes incorporating what appears to be a self portrait of the artist in close up, peering into the scene. His portraits of soldiers suffering from psychological trauma draw powerful attention to their wide-eyed or blank stares. From these portraits Tucker drew out and distilled the key element of wide, stricken eyes to create a more expressionistic view of internal anxiety and trauma. The pervading visual and psychological elements of Tucker’s Wangaratta and Heidelberg hospital drawings and paintings find their apotheosis in his 1942 painting The possessed. Here we witness a figure with a twisted body, single staring eye and mouth gaping in delirious laughter or screaming horror, confined within a vividly coloured cell-like room. The image is a powerful representation of psychological trauma and isolation.

For Inner Worlds a significant group of Tucker’s ‘psycho’ portraits and related works have been loaned from the Australian War Memorial, the National Gallery of Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria. They are vivid and intense and convey a powerful sense of concentrated emotion that continues to speak to us across the decades. University of Queensland Art Museum Until 23 October 2011 Ian Potter Museum of Art 18 April – 22 July 2012