Dix’s mastery in turning his intense observation of people into images of types that characterised German society during the turbulent years of the Weimar Republic is celebrated in an exhibition focusing on Dix’s portraits at the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart (formerly the Galerie der Stadt Stuttgart).

Including sixty-six portrait paintings by Dix and numerous works by artists ranging from Lucas Cranach to Andy Warhol, the exhibition explores Dix’s unique approach to portraiture within the context of art across the ages, from the ancient through to the present day. The ultra-modern, three-level special exhibition space at the Kunstmuseum lends itself to this kind of thematic as well as chronological display, which ‘concentrates on portraiture as artistic convention’.

On the first level, fascinating comparisons can be made when encountering an Egyptian mummy portrait and portraits by Cranach alongside Dix’s images of women and his family. These unusual juxtapositions offer insights into issues of form, composition and technique as Dix very consciously placed himself in the tradition of his art-historical predecessors, particularly the German old masters. It is interesting to observe that Dix was inspired by the timelessness and directness of ancient mummy portraits, yet the formal similarities between Cranach’s portraits and Dix’s portrait of his three-year-old son Ursus sitting, for example, are more striking. Dix admired the ‘unbelievable simplicity’ of Cranach’s compositions and the stark concentration on the physical appearance of Ursus – his light hair, skin and clothing contrasting dramatically with the dark neutral background – highlights Dix’s interest in early sixteenth-century German painting. Dix’s unique and consistent use of tempera and oil painting, often on wood panel, is another fascinating yet unexamined aspect of Dix’s work.

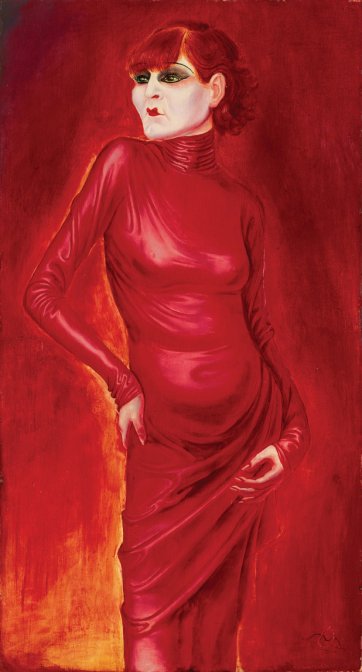

One of the highlights of the exhibition is Dix’s representation of women, ranging from the very elegant and flattering portrait of his wife, Martha Dix, to the astonishing portrait of the dancer Anita Berber, undoubtedly one of his greatest Berlin portraits. Berber perfectly encapsulates Dix’s ability to distill the physical attributes of the legendary dancer described by one commentator as ‘the most extreme woman of her day’ into an image embodying Weimar decadence and subversiveness. The intense concentration upon Berber’s heavily made-up face and red puckered mouth, her slinky red dress accentuating her highly eroticised body and her clawlike painted nails set against a similarly red-hued background combine to create a captivating but also disturbing image of the 1920s femme fatale. An extraordinarily daring and charismatic performer but also a cocaine and opium addict who lived life on the edge, Berber died just three years after this portrait was painted at the age of twenty-nine.

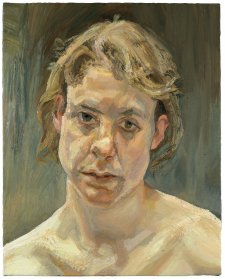

The exhibition curator, Daniel Spanke, a portrait specialist based at the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, emphasises the importance of direct observation and faithfulness to reality in the work of Dix and the New Objectivity artists. To Dix, a critical part of this process was preserving his first impression of people, commenting that ‘The first impression of a person is the right one’, even if that impression resulted in the representation of an aspect of reality that artists had previously avoided: ugliness. Dix’s complex relationship with modernism is explored through a stylistically diverse group of works by his contemporaries – including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Rudolf Schlichter and Karl Hubbuch – exhibited on the second floor of the exhibition. These artists shared Dix’s interest in capturing intense expression and contemporaneity, regardless of whether their work was related to any single tendency in modern art – Expressionism, Cubism, Dada or New Objectivity.

Another interesting idea that the exhibition features is the perceived difference between the painted and the photographic portrait. Dix was vehemently opposed to photographic portraits as only able to capture a single moment whereas, he argued, painted portraits were able to capture the whole person. These contentious remarks beg us to ask the question, how do Dix’s portraits, which simultaneously depict his sitters as real individuals and as types, differ from August Sander’s photographs of the German people, which equally offer a collective portrait of the Weimar era? There are several photographs by Sander in the exhibition, including the breathtaking Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne 1931 and Wife of an Architect (Dora Lüttgen) 1926, both of which typify the ‘new woman’ found in numerous portraits by Dix, suggesting that he might have seen himself in competition to photographers of the period.

Contemporary portraits made since 1960 are displayed on the third floor of the exhibition, by artists as diverse as Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter and Thomas Struth, offering further opportunities to explore issues related to portraiture in contemporary art. Four works by Warhol deal with the relationship between ‘image’ and ‘person’, and mark the revival of the portrait in contemporary art. The directness and monumentality of Thomas Ruff’s portraits are qualities to be found in Dix’s portrait The Actor Heinrich George, also included in the contemporary section. What strikes the viewer about this work is the penetrating gaze of the actor, with his icy-cold stare and his overpowering physical presence.

Dix again recalls the art of the sixteenthcentury German masters through his extremely fine painting technique and inclusion of a Latin inscription that gives the name and age of the sitter. This work is a powerful reminder of the central theme of the exhibition, that nothing captures our attention so strongly as the sight of another person and that through this intense experience of seeing we are simultaneously locked into the past and present moment.

That this is the first exhibition to concentrate on Dix’s portrait painting adds special importance to the exhibition, as portraiture accounts for such a large and significant aspect of the artist’s oeuvre. It is highly relevant that the Kunstmuseum stage this exhibition, as it houses one of the world’s largest holdings of work by Dix, including Prager Strasse 1920, The Salon I 1921, Three Wenches 1926 and his iconic Metropolis (Triptych) 1928. Even if you do miss this insightful exhibition, a trip to the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart at any time is highly recommended!