One of the most intriguing contributors to Australian Pop art is Sydney born and based artist, Martin Sharp AM (b. 1942). As an artist, writer, cartoonist, graphic artist, songwriter and filmmaker, his work became synonymous with the rising counter-culture of both Sydney and London in the 1960s and 1970s.

It was immediate, bold, often ironic and easily available through reproductions on album covers, posters and various newspapers and magazines. Martin Sharp is represented in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery as both an artist and a subject, with these images revealing his prolific involvement with the art and culture of the period.

In the early 1960s Sharp joined with Richard Neville and Richard Walsh and founded Oz, a satirical and controversial magazine that was contemptuous of conservative and mainstream Australia.

Using cartoons and cleverly written articles packed with colloquialisms, regular contributors to Oz lashed out at Australian and international politics and confronted such taboo topics as abortion, the pill and recreational drugs. They had a dig at the architecture of Harry Seidler while supporting Jørn Utzon’s at the time controversial Sydney Opera House. One of Sharp’s front cover drawings depicted Boofhead, the ultimate Australian simpleton, accompanied with the speech bubble, ‘…but I don’t give a stuff about Opera’. Sharp’s cartoons were a feature of Oz and were scattered throughout its pages. His sketchy pen drawings were accompanied by witty one-liners, using the subverted humour of the cartoon tradition to great effect.

The editors of Oz easily managed to stir the pot of conservative Sydney. Censorship of literature still prevailed in Australia in the 1960s and the February 1964 edition was found to have breached the Obscene and Indecent Relations Act of 1901. Neville, Walsh and Sharp were able to successfully appeal gaol terms, yet the stifling provincialism of Sydney began to take its toll. Sharp started finding opportunities elsewhere.

In 1965 Sharp held his first one man exhibition, Art for Mart’s Sake at the Terry Clune Gallery. It was a successful show, but Sharp soon joined a string of Aussie expats living in London during the swinging sixties. The counter culture of London was conducive to Sharp’s increasingly psychedelic style and collage process of art making. He took up a studio in The Pheasantry on King’s Road, Chelsea, a haven for artists and musicians.

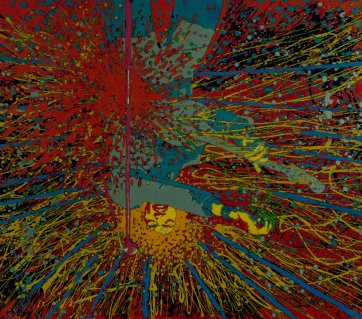

By chance he formed a friendship with Eric Clapton, guitarist for the supergroup, Cream. Clapton converted one of Sharp’s poems, Tales of the Brave Ulysses in to a song, which featured on the album Disraeli Gears. Sharp created the iconic cover art for this album and Cream’s next, Wheels of Fire. These album covers are a psychedelic fusion of disparate images and swirling text in clashing, day-glo colours. Clapton also introduced Sharp to the music of troubadour and recording artist, Tiny Tim, who has remained a powerful influence on Sharp. He also created posters for musicians, Donovan, Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix, as well as protest posters, for such events as the Legalise Pot rally. These evoke LSD trips, with the hallucinatory quality of the graphics enhanced by printing on silver and gold foil.

Richard Neville had also arrived in London, ready to kick start London Oz. With Sharp as the artistic director, the reincarnated magazine soon gained the notoriety of the Sydney years. Sharp’s London posters and album covers are instantly recognisable as the embodiment of psychedelic pop art. His contribution to the visual imagery of the 1960s was recently recognised in an exhibition, Sixties Graphics, held at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Sharp returned to Sydney in 1969. He soon instigated a new project in a building that was marked for destruction, the old Clunes Gallery at Potts Point. The resulting Yellow House was, Sharp declared on ABC TV ‘probably one of the greatest pieces of Conceptual art ever achieved’.

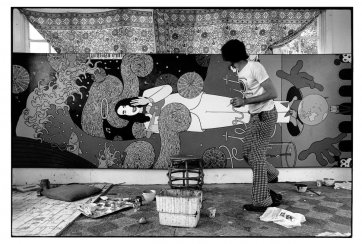

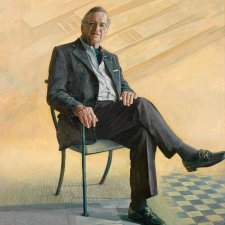

Sharp had been inspired by Vincent Van Gogh since his teen years. The Yellow House drew motivation from Van Gogh’s studio at Arles, France and the desire to create an artists’ community. Numerous young Sydney artists were involved in the project, all contributingto the ever-evolving themes of the house. Exhibitions, puppetry plays, film screenings and theatrical performances were all a feature, as were specific rooms that paid homage to modern art masters. In 1971, Greg Weight photographed Sharp in the Stone Room. Sharp’s image is framed by moody shadows, a copy of Hokusai’s famous wave print in the background. Dressed in geometric patterned clothes and a knitted beanie, Sharp holds a copy of The Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Dickens. The prop indicates Sharp’s own inquisitiveness about art and popular culture, but also a growing public curiosity about Sharp and the Yellow House.

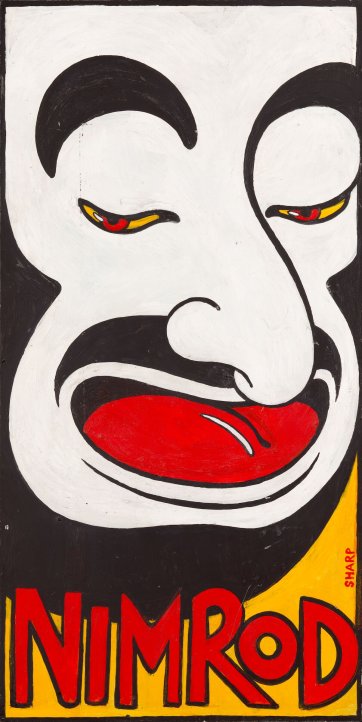

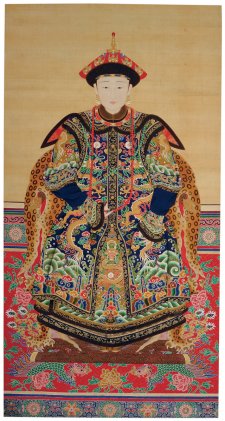

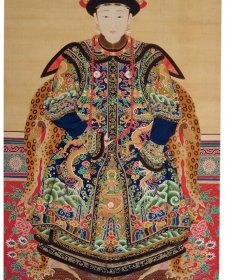

During his time in London and upon his return to Sydney, Sharp was working on a series of collages, or artoons. He would slice up pictures of European masters and then paste them into new settings, recontextualising both works, but also establishing unified artistic intentions of the original pieces. The same free association was used in Sharp’s 1977 painting, Young Mo (Ro Rene) that was created to promote the play Young Mo, showing at Sydney’s Nimrod Theatre. The play starred Garry McDonald, who was wildly popular at the time as Norman Gunstan. The portrait references the black and white painted faces of vaudevillian duo Stiffy and Mo, created by Australian performers, Henry van der Sluys and Neil Philips. It merges their painted masks with a print of a Japanese Kabuki actor and incorporates the facial features of McDonald. The painting was reproduced as a poster and the image became synonymous with the theatre company.

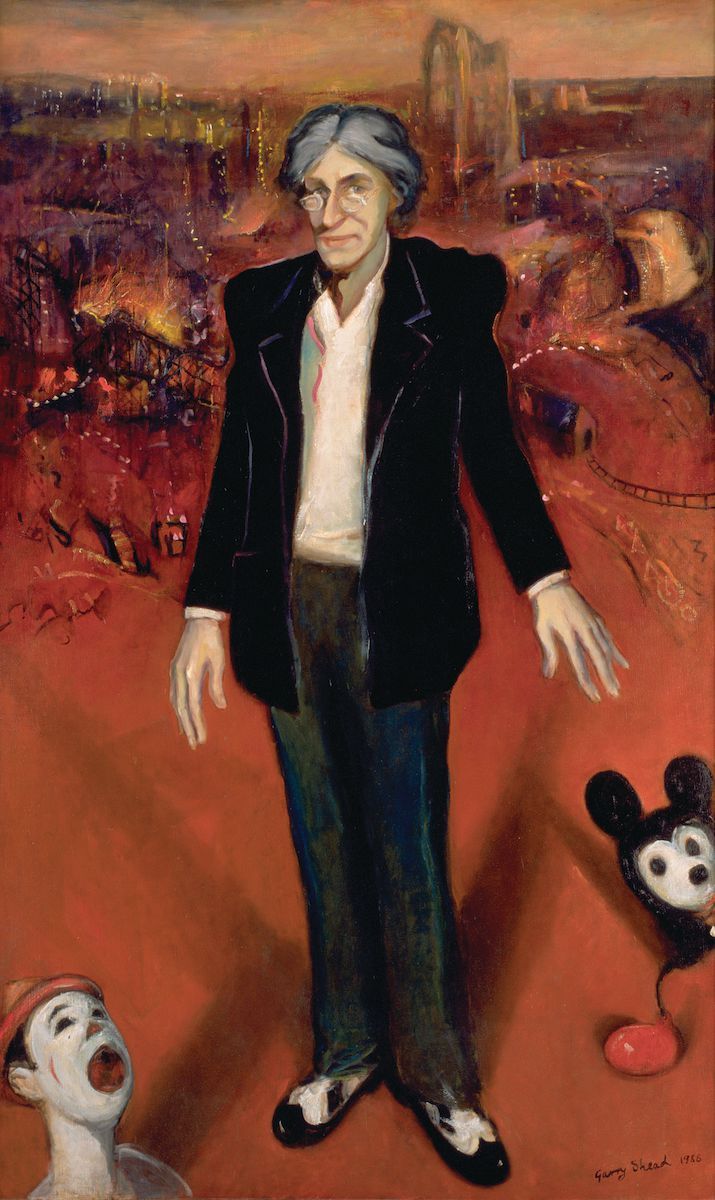

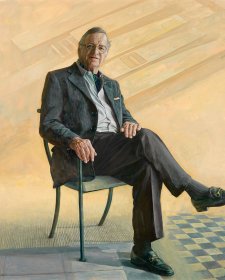

Martin Sharp has remained occupied by Sydney icons throughout his career, in particular, Luna Park. In the mid 1970s, Sharp was one of three artists commissioned to redecorate the entrance towers and massive smiling face of Luna Park. His passion for preserving the cultural landmark is expressed in Garry Shead’s unsettling and despondent portrait of the Pop artist, which synthesizes several of Sharp’s artistic themes from the 1970s. Sharp stands in the foreground of the painting and his figure casts dual shadows. This spotlight effect places Sharp centre stage to the fate of Luna Park. Mickey Mouse, who had appeared as jovial in one of Sharp’s earlier collages, now peeks apprehensively at the viewer, his hand reaching out of the canvas and on to the edge of the frame. The mouth of the sideshow clown is forever locked open in a scream. The clown is a witness, like the viewer, to the scene in the background that depicts the tragic Ghost Train fire of 1979, in which seven people were killed. Sharp firmly believes the fire was an act of arson. He and artist Peter Kingston formed the Friends of Luna Park to restore the site, and his relationship with it persists as he continues to live and work in Sydney.