George Walker’s Durham directory and almanack of 1850 has an interesting frontispiece. The view is not of the imposing Norman cathedral, nor of the picturesque woods and gorges of the River Wear, but is much more domestic and familiar: a view of the town marketplace.

It was common practice for publishers and printsellers at the time to re-use old blocks, and Walker inscribes this print as a view from 1830. At first sight a pedestrian image, in the somewhat coarse manner of British popular woodcuts, inspection reveals it to contain a surprisingly rich lode of information.

To begin with, it is of antiquarian interest. St Nicholas’ Church in the background is the original 12th century structure, complete with its adjacent market arcade. Deemed ‘an eyesore and a disgrace’, the old church was demolished in 1857 and replaced by the present building, a neo-Gothic design by J.B. Pritchett. The marketplace’s well-known bare-bottomed King Neptune is there, too, a symbol of the city’s 18th century ambitions to connect the River Wear to the sea. But, in the woodcut, Neptune stands on his original base, a pant that supplied fresh water, piped across the river from Fram Well.

Of equal interest to these records of architectural heritage are the figures that populate the square. Two are clearly identifiable as well-known local ‘characters’ from the 1820s. In the left foreground, worried by a dog, is Tommy Sly, a resident of the Durham poorhouse. A contemporary account described him as ‘… “daft” … he dresses in a coat of many colours, attends the neighbouring villages with spice, some days parades the streets of Durham with “pipe clay for the lasses”, and on “gala days” wanders up and down with a cockade in his hat, beating the city drum, which is goodnaturedly lent him by the corporation’. On the other side of the print is the town’s famous crier, the one-armed, eccentric and bibulous bellman, Hut (Hutchinson) Alderson.

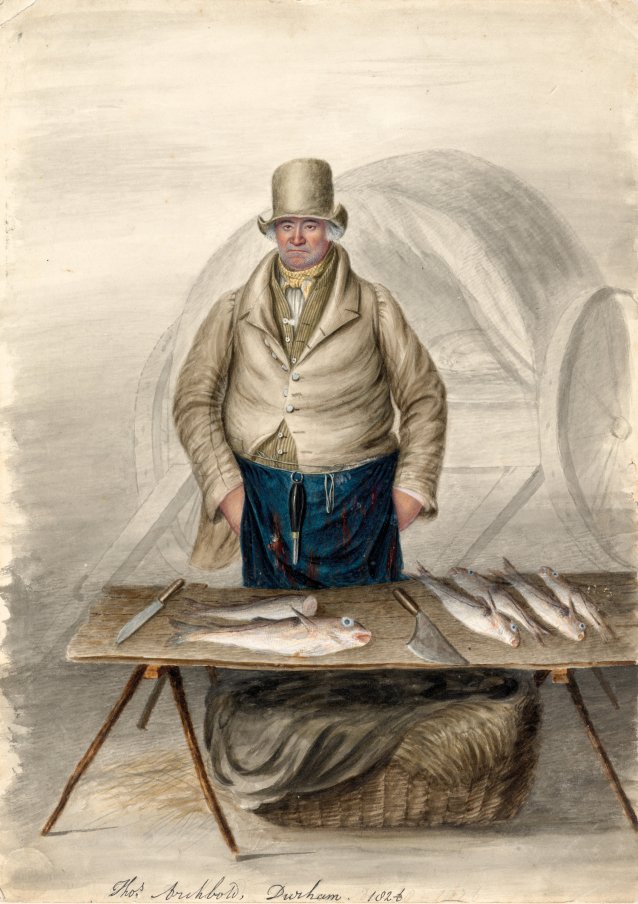

In addition to these ‘living features in (Durham’s) scenery’, the Almanack print incorporates a covered wagon standing on the north side of the market square, probably that of the fishmonger, Thomas Archbold. Dempsey’s portrait shows this familiar street trader with his cart, trestle and basket; his knives, steel and apron; and his array of fine gurnards.

Little is known of Archbold’s early life beyond the bare facts of parish records: his birth in Low Friarside in 1757; his two marriages (in 1788 and 1801) and the birth of his four offspring (1790, 1794, 1802 and 1803). How he came to leave his earlier employment on the land (parish registers describe him as ‘labourer’ and ‘husbandman’) to become the proprietor of a fish wagon is unknown, but an inscription on this drawing suggests he had been selling fish in Durham since 1810. John McKnight was the only fishmonger in Durham in the late 18th century but, by the 1820s, the prosperous cathedral town of 10,000 souls could clearly support more. In the Durham directory for 1827, Archbold is one of three; the McKnight family is still in business in Sadler Street, but they now have competition from Archbold and from Thompson, both of Gilesgate. There being no substantial shops on Gilesgate, it must be assumed that Archbold sold his wares from the cart in the streets or at the town’s Saturday market. In any event, the visibility, mobility and capacity of the wagon seem to have served Archbold well. By the time of the 1841 census he was comfortably retired, being described in the returns as a householder ‘of independent means’. Although Ann, his second wife, had died in 1837, Thomas was not alone; living with him at the time were his son George, daughter-in-law Isabelle and grandchildren Thomas, John, Mary and Isabelle.

Thomas Archbold died on 24 May 1844, and was buried at St Giles’s Church. That he was evidently well-known in the town is attested by the fact of his being accorded the dignity (rare for one of his class who was not distinguished by longevity, eccentricity or criminality) of an obituary in the Durham Chronicle.

Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, presented by C. Docker, 1956