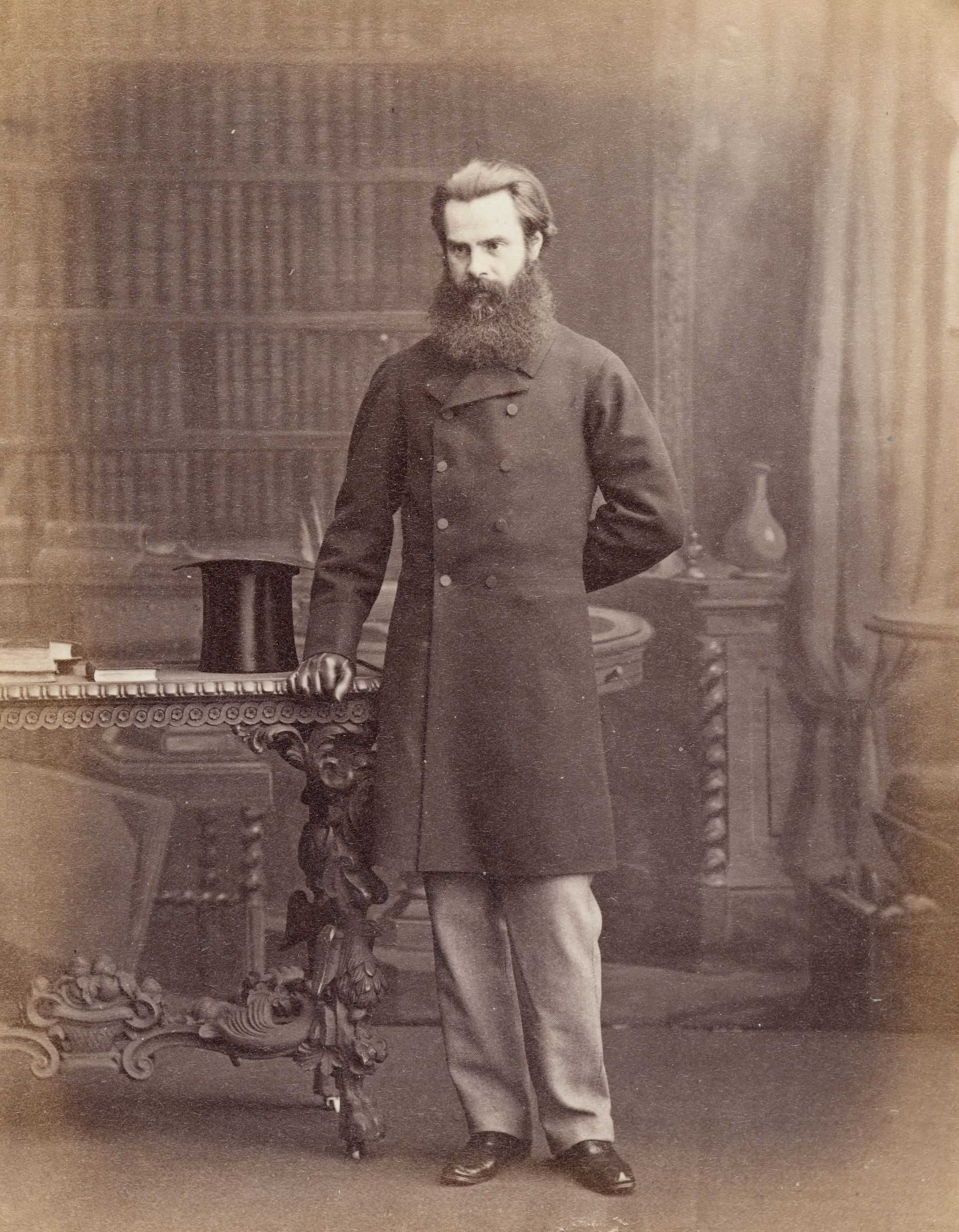

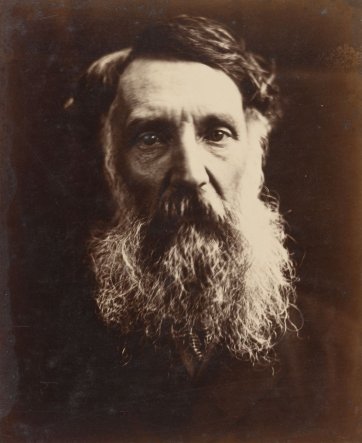

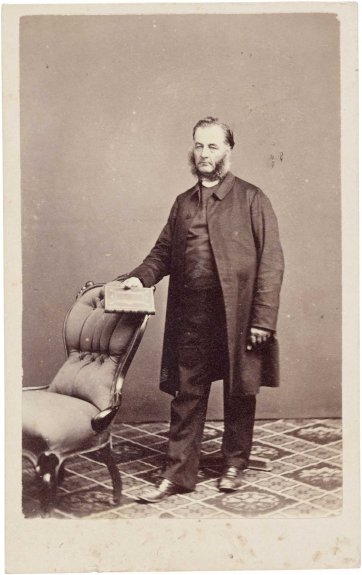

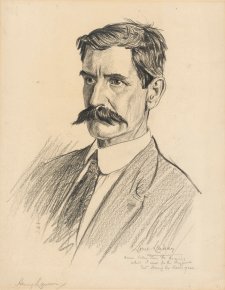

The restrained and cultivated facial hair fashions evident through the first decades of the 1800s were on the wane by the middle of the century, when hirsute faces became mainstream. The period from the 1850s to the 1880s is one characterised by greater diversity in men’s hairstyles and is distinct in particular for the renaissance of beards: long or short; tidy or unkempt; with or without side whiskers and moustaches. Historians have put this trend down to a combination of factors that resulted in beards being considered an outward, physical expression of the masculine attributes most prized in Victorian times. The flipside of attitudes that enshrined characteristics like demureness, vulnerability, and chastity in women were those that measured male worthiness in dignity, decisiveness, independence and virility.

Hairiness, by this reckoning, was next to manliness. With the failure of liberal revolutions in Europe in 1848, beards lost their association with radicalism. They were consequently adopted by men of all classes and in numerous styles – something that a survey of famous nineteenth century faces demonstrates. Abraham Lincoln with his trim, chinstrap style fringe beard; Charles Dickens, whose clean shaven cheeks terminated in a beard joined to a generous moustache; the long, philosopher-like beard worn by Charles Darwin; or the vigorous, bushy style sported by locals Robert O’Hara Burke and Ned Kelly. Sideburns – named after the Civil War general, Ambrose Burnside – also grew longer and more luxurious. For example, Burnside’s ‘mutton chop’ style, where whiskers broadened across the cheeks and met in a moustache, was popular; and the style known as ‘Piccadilly Weepers’ – very long, comb-able, pendant whiskers – came into being in the 1860s.

The so-called beard movement of the 1850s saw the promotion of beards on various grounds, including that they were a sign of strength (think Samson) or sageness (Socrates et al); and that they distinguished ‘real’ men from their effete or otherwise questionable contemporaries. Religious arguments proposed that shaving was somehow sinful as a means, for example, by which gender distinctions might become blurred. Facial hair was also argued to have benefits for health and hygiene. ‘For the man who goes out to his labour in the morning’, stated an essay published in Dickens’ journal Household Words in 1853, ‘no better summer shield or winter covering against the sun or storm can be provided.’ Beards and moustaches, it was argued, had the effect of filtering out smoke, dust and pollutants. Shaving therefore was ‘a painful, vexatious and not merely useless but actually unwholesome custom.’

In Australia, beards could be emblematic of a frontier ethos. Explorers, bushmen, squatters, gold-seekers and others whose existences took them beyond the settled, civilised districts adopted beards for reasons of practicality as well as for ideals of ruggedness, independence and masculinity. Others, including bushrangers like Frank Gardiner (‘black curly hair; whiskers and moustache; dressed in cabbage tree hat, black poncho, long thigh boots’ according to the NSW Police Gazette in June 1862), consciously favoured the ‘flash’ moustachioed look that symbolised defiance or rejection of polite convention.