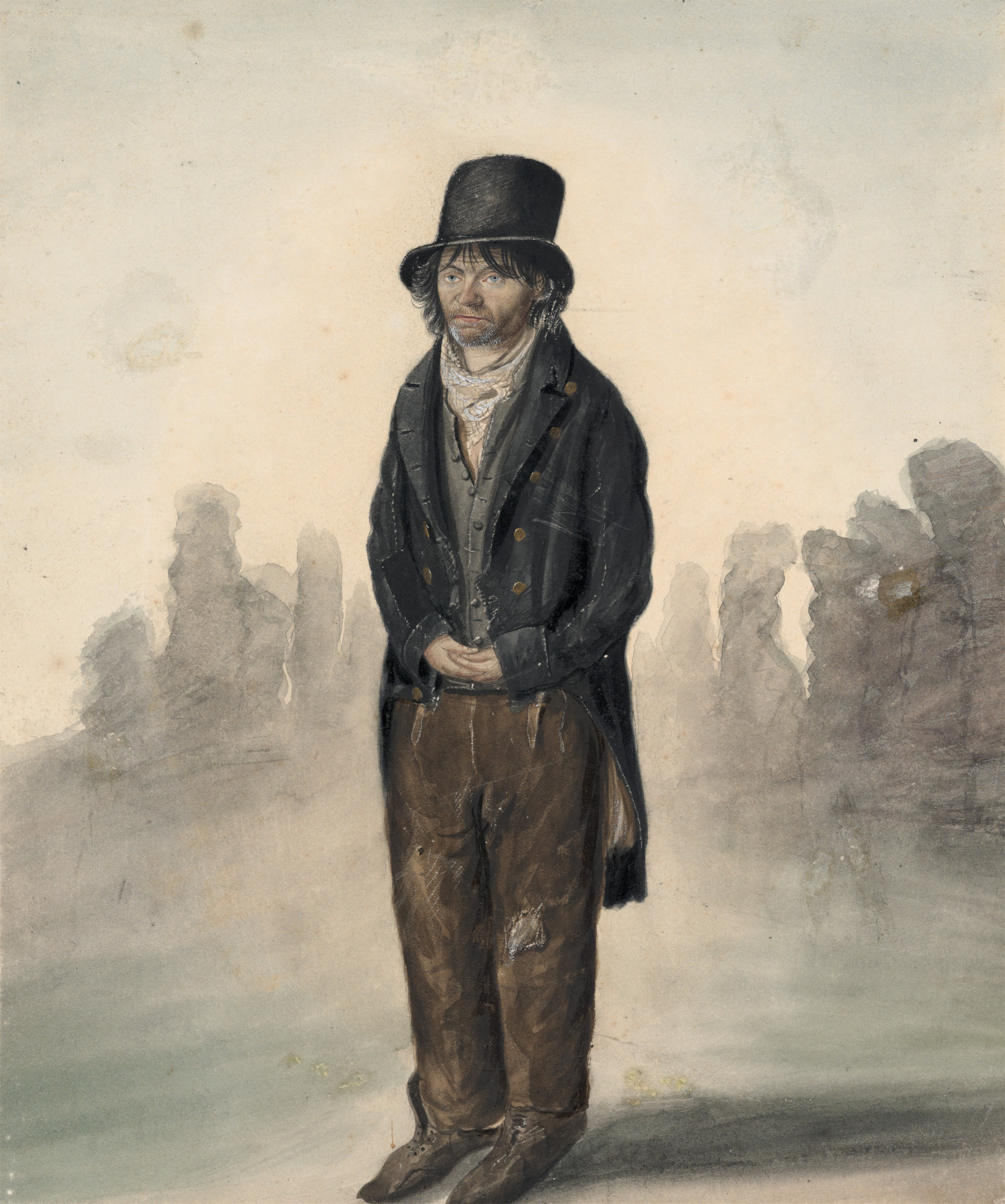

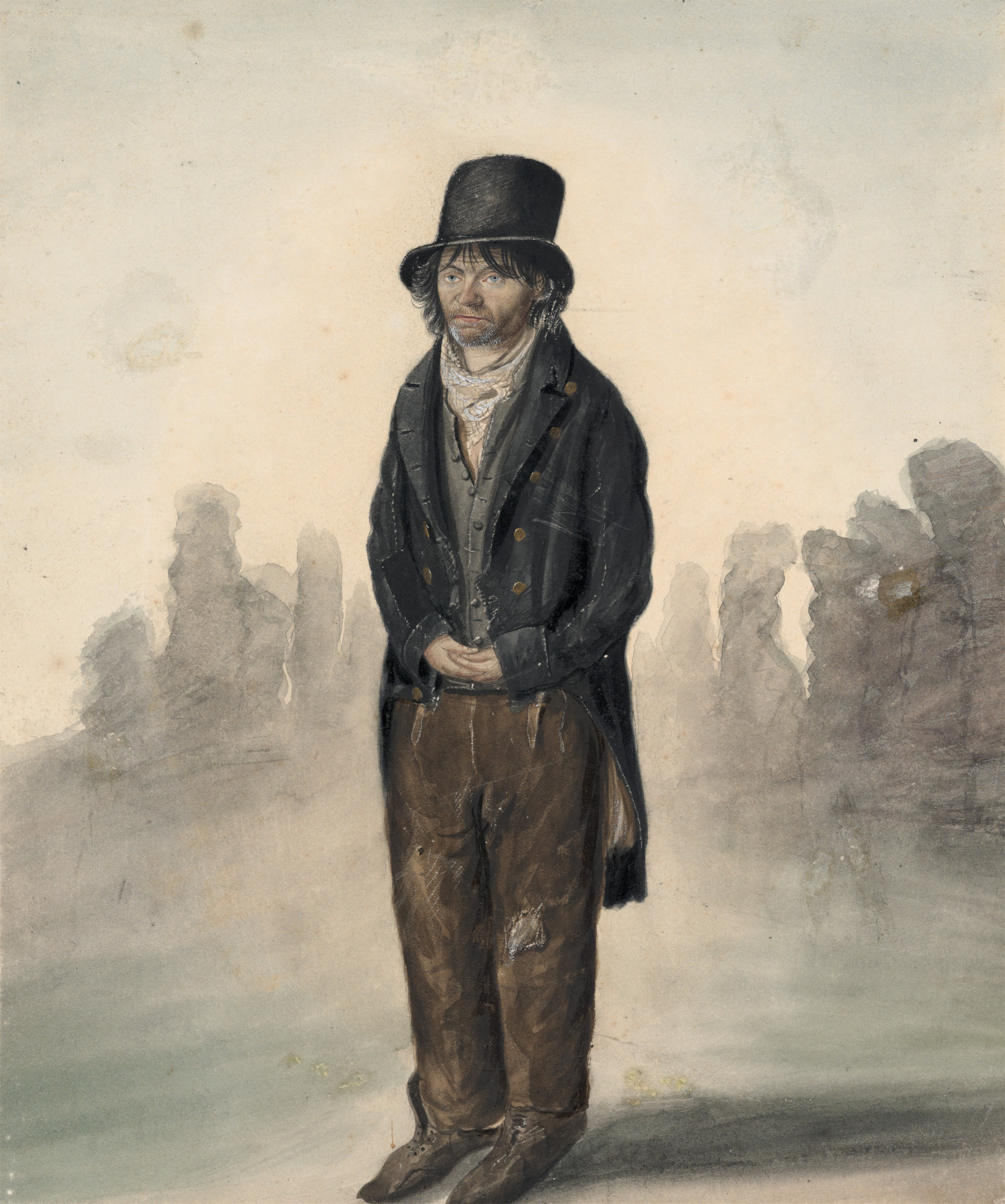

Little John of Colchester, a poor lunatic, c.1823 by John Dempsey

Those of you who are active in social media circles may be aware that through the past week I have unleashed a blitz on Facebook and Instagram in connection with our new winter exhibition Dempsey’s People: A Folio of British Street Portraits, 1824−1844 (Thursday 29 June until Sunday 22 October 2017). As the exhibition curator David Hansen points out in his beautiful catalogue essay, it is a sad irony that this lovable artist, John Church Dempsey (1802/03−1877), to whom we owe so much for preserving the mostly humble, certainly fugitive identity of 54 individuals (an unusually large proportion of whom are known and named), should himself remain so shadowy a figure. Much of what we know about him is contained in his surviving portraits, of which a folio of 51 was in 1956 presented by Conrad Docker to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart, and another ended up in the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa in Wellington. This is the first time that they have been shown as a complete set.

For many years I visited London and the UK regularly and often. Inasmuch as London is today a global metropolis of unparalleled diversity, it is also true that from time to time, walking down Strand or Haymarket or the Marylebone High Street, you would come face to face with someone you swore had stepped straight out of Holbein or Van Dyck. Dempsey's People produces a similar effect, though in reverse. Unknown individuals, mostly humble, even destitute, can feel eerily familiar, as if nearly 200 years and 10,000 miles simply evaporate. Where is the membrane that separates the plain, the ordinary, the urban poor of Regency England—perforce the virtual ancestors of many Anglo-Australians—from remarkable characters and truly compelling, certainly memorable presences? Though it wobbles, I think John Church Dempsey very ably took the measure of that membrane, which is no small achievement. I cannot overstate the quality of David Hansen’s scholarship. Those of us who are old enough to remember the “New Art History” will recognize it in this exhibition.

1 Billy Bean, Butchers’ carrier, Scarborough, 1825. 2 Mary (or Elizabeth) Leagrove, attendant at the gaol, Ipswich, c. 1823,. Both by John Dempsey.

A curious feature of the Docker folio is that 23 of the 51 sheets are unequivocally dated (45%). Of these, all but two (41.1% of the entire folio) cluster into the period 1823–25. Nine sheets are dated 1823, when John Dempsey was only twenty or twenty-one years old. Ten are dated 1824, and three 1825. 1823 fixes Dempsey in East Anglia for the most part, but down in Hampshire also. In 1824 he is in London and the Midlands. By 1825 he is up north, in the East Riding of Yorkshire and County Durham. (One of the few adverse consequences of Harold Wilson’s rearrangement of English county boundaries in the 1960s is that they no longer align with the immensely long historical record, but that is neither here nor there.)

It may be that Dempsey’s excellent habit of dating his sheets was a product of youthful meticulousness, but it is a pity that he soon abandoned it. Between 1826 (back in Durham) and 1844 (Dickey Fletcher in Liverpool) we have no concrete dates at all, only approximations thanks to careful digging, inference and David Hansen’s, if I may say so, fine connoisseurship. The more you look at him, the more fascinating John Church Dempsey becomes. And you begin to catch what in turn caught his eye, above all buttons (often mismatched out of necessity), ad hoc stitching, patches, shoe laces, useful leather straps, holes in stockings and shoes, old gaiters straining against swollen calves and gouty ankles. If there are umpteen different words for snow in Eskimo, in Dempsey there are as many ways with fraying cloth.

1 Richard ‘Dickey’ Fletcher, bellman, Bridlington, c. 1825,. 2 Ann ‘Old Nanny’ Chapman, Bury St. Edmunds,. Both by John Dempsey.

The weight of evidence suggests that, whatever merely adequate training he received, Dempsey was a painter of miniatures. The quality of his faces and his attention to matters of the finest detail appears to lend credence to this hypothesis. Here, therefore, Dempsey was working on what was for him a colossal scale, and there is no doubt that at times he struggled with proportion, spatial relationships, and—no doubt about it—feet. So why did he paint these portraits, and keep them? We think we know. Prior to the invention of photography, if you lived in Ipswich in the early 1820s you did not necessarily know exactly what the Duke of Wellington really looked like, so fame—such as it was—was more likely to adhere to the strictly local, above all the curious, often eccentric characters that were known to everybody on the streets of town, the gaol attendant for example with her definitely arresting presence. If an itinerant portrait painter like Dempsey wished to demonstrate his skill, he could do far worse than to select such a person the better to garner business from the local gentry, townspeople, and other clients for whom the great London portrait painters such as Sir Thomas Lawrence were out of reach.

John Church Dempsey was merely one ordinary foot soldier marching in the ranks of a huge battalion of artists and makers, labouring away in every corner of Regency Britain, who are today, like so many of their subjects, all but forgotten and mostly excluded from the historiography of British art. One might put it slightly differently and say that the most important thing about Dempsey and his people is that none of them was important.

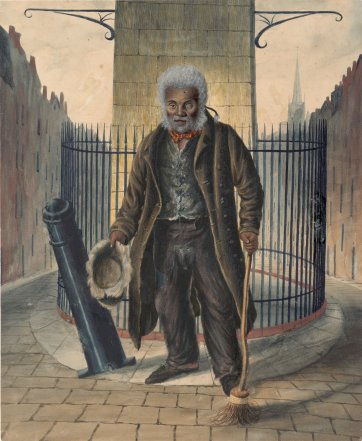

1 Portrait of John Rutherford,. 2 Charles McGee, crossing sweeper, London, c. 1824,. Both by John Dempsey.

History tends to ignore the lowly. Those who dwelt at the fringes of society, or among the ranks of sick and poor or destitute, have rarely left more than the faintest mark upon it, more usually none at all. We can therefore be justly proud that Billy Bean and Mary Leagrove and John Rutherford and Charles McGee and Old Nanny Chapman and Dickey Fletcher are accorded here the dignity of being at least partly rescued from that historical oblivion, together with many of their humble occupations and even certain of their scrapes. We may now recognise them once more, as we know their neighbours did.