It mirrored the treatment accorded their antecedents as so-called ‘New World ambassadors’; the Cherokee warrior Ostenaco (c. 1703–1780), for instance, and the Mohawk politician and military leader Thayendanegea, or Joseph Brant (1743–1807), who both travelled to London in their roles as colonisers’ allies. Truettner notes that official Native American visitors to Washington in the early decades of the nineteenth century partook of various dinners and social gatherings, and sightseeing tours that included ‘stops at the Capitol and other imposing federal buildings, and at the Navy Yard, where frigates saluted the visitors with round after round of cannon fire, a none-too-subtle reminder of the power whites could direct against Indians’. It was usual, too, for the visitors to be presented with peace medals as a signifier of amity and allegiance.

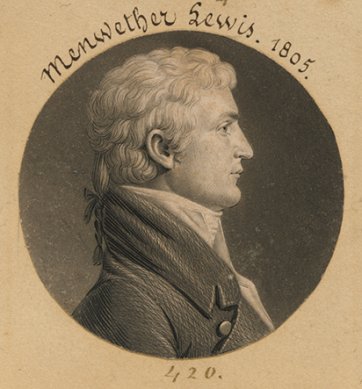

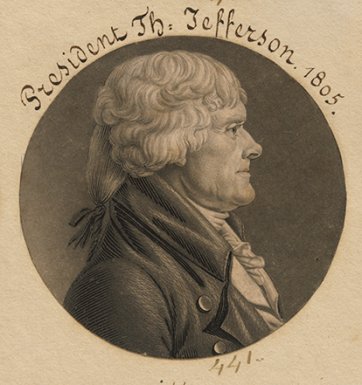

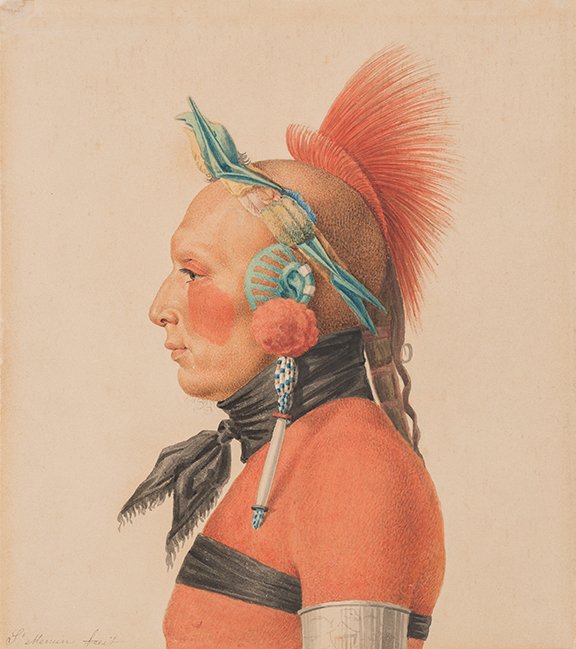

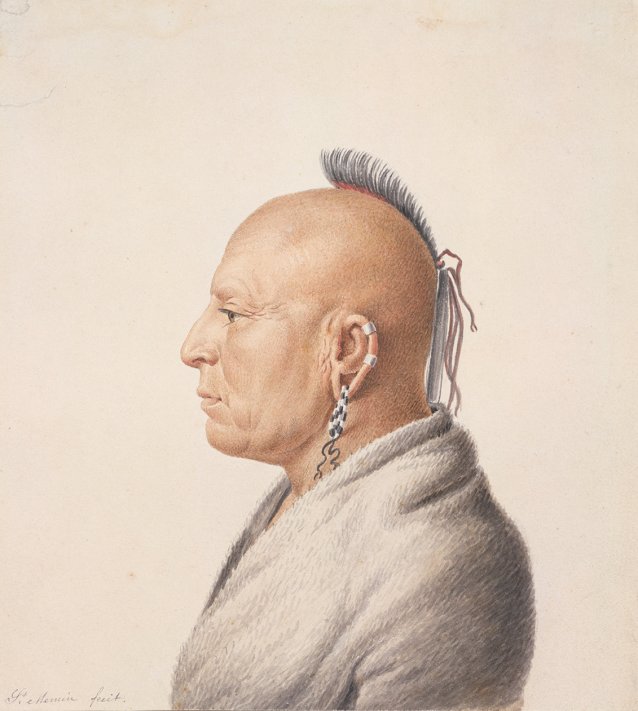

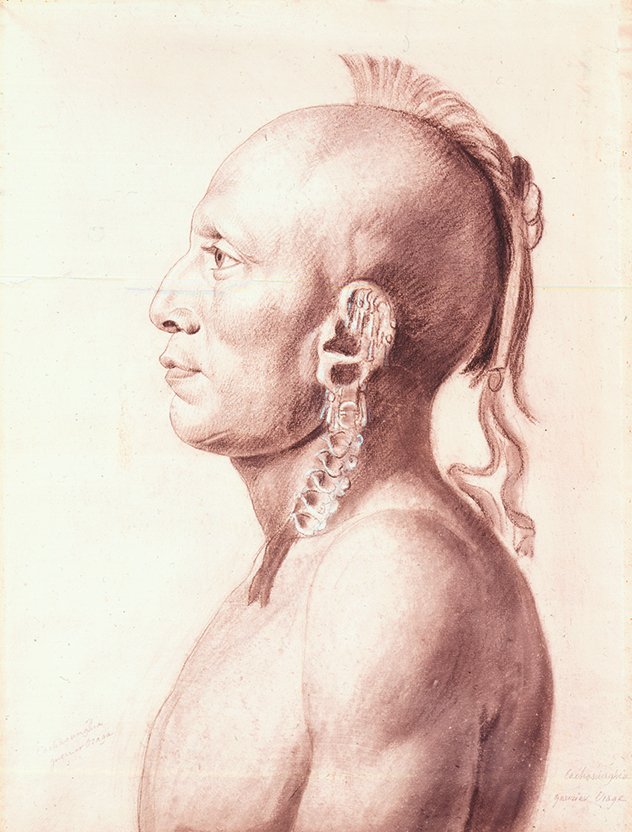

Sittings with portrait artists also became a feature of the schedule, the resultant likenesses similarly evincing the dual motives behind these statesponsored visits from what Bayard Smith termed ‘our savage brethren from the woods and wilds of the Far West’. As Truettner elucidates in his study, Painting Indians and Building Empires in North America 1710–1840, the images of Native Americans made by European artists in this period constituted an exercise in ‘portrait diplomacy’, whereby portraits and other outward displays of peace and friendship operated in tandem with moves towards the implementation of an increasingly imperialist agenda in the decades following American independence. Consider as an example the fifteen portrait drawings made between 1804 and 1807 by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, which, as Truettner notes, appear to have initiated the practice of formally documenting members of Native American delegations. This group of works constitutes a small fraction of the artist’s output, yet they amount to an instructive case study in the importance of not always taking portraits at face value.

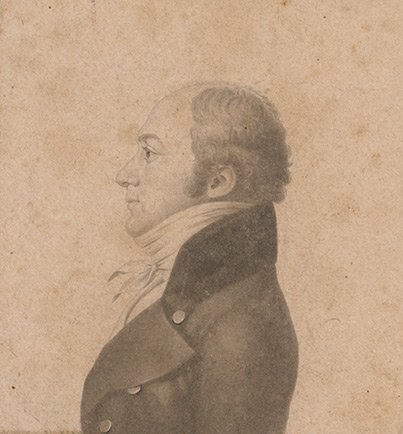

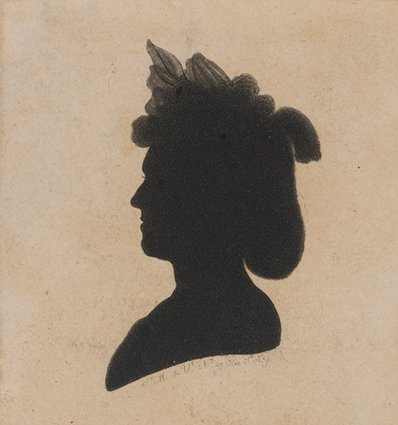

A former soldier, and of aristocratic origins, Saint-Mémin (1770–1852) had fled his native France when his family’s estates were confiscated in the early years of the Revolution. In 1793 he and his father ended up in New York, where, finding himself without an income, he decided to take up portraiture. By early 1797, having learnt engraving techniques, he was working in partnership with another French émigré, Thomas Bluget de Valdenuit; the pair advertised that they were supplying ‘Portraits on an improved plan of the celebrated Physiognotrace of Paris’, a pantograph-like apparatus that facilitated the speedy creation of highly accurate (and therefore most desirable) profile portraits. ‘From the expedition with which the work is done, and the moderation of terms,’ the advertisement continued, ‘[the artists] presume to hope that they will give satisfaction to those who … will please to encourage them with their commands.’