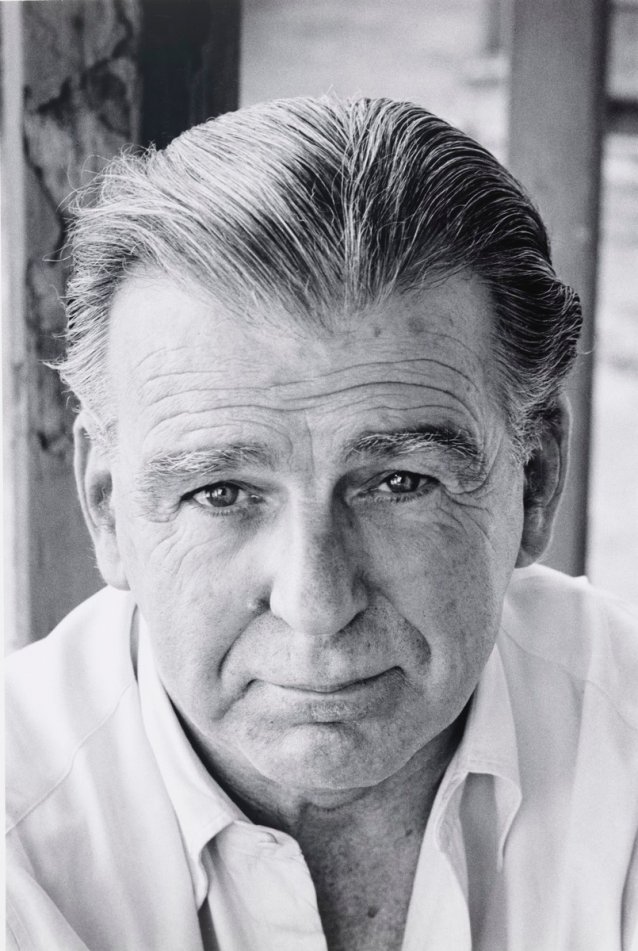

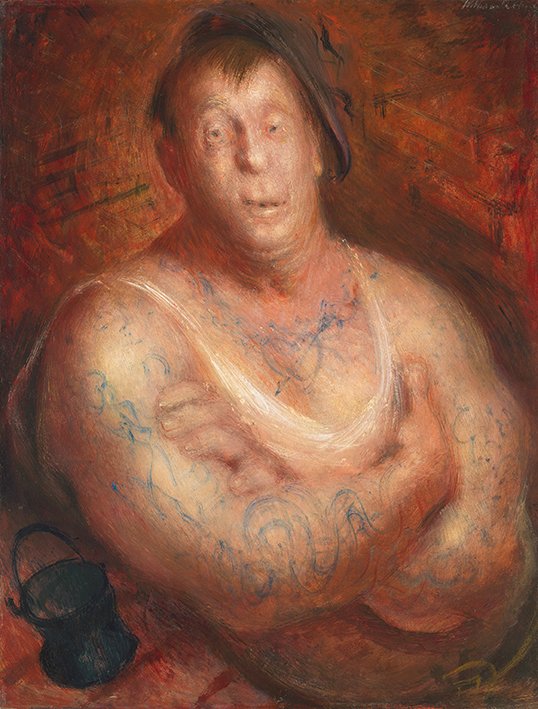

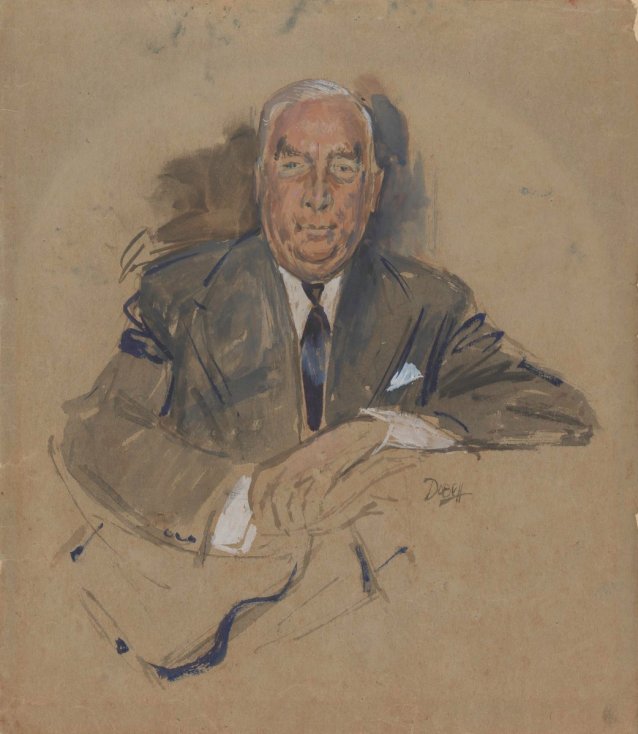

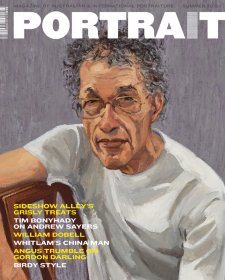

Edward MacMahon’s relationship with ‘Bill’ Dobell began remotely in the early 1940s, when, having operated on an impecunious Sydney jeweller, MacMahon was constrained to accept a painting of Dobell’s as payment. The jeweller, himself, had acquired the painting from Dobell in exchange for a watch repair. Sometime later, Frank Clune brought Dobell to MacMahon’s house to see the painting, and the friendship between Dobell and MacMahon began. In 1957, the year of his astounding portrait of Dame Mary Gilmore (‘This work will still be carrying my identity when my own work is forgotten’, she predicted, accurately), Dobell was diagnosed with bowel cancer, and in 1958 MacMahon performed two difficult operations on him. The men spent much time together during Dobell’s long convalescence in St Vincent’s, and their friendship intensified. In the second half of that year Dobell made a start on MacMahon’s portrait, making innumerable pencil sketches, and studies in watercolour and oil that are now owned by the MacMahon siblings. The studies for the portrait show MacMahon in ordinary clothes, not surgical garb, although when Dobell was questioned about the significance of the splash of red in the painting he denied that it was an allusion to MacMahon’s sanguinous profession, and claimed it was simply a patch he forgot to paint over. This painting won Dobell his third Archibald, in 1959. ‘Dr MacMahon is an enormous person. I owe everything to him’, said the artist, who was a regular in the doctor’s circle for the rest of his life and is warmly remembered by MacMahon’s sons and daughters.

From this period on, Dobell enjoyed great success and renown as a portraitist. At the age of 59, after 55 hours' instruction, he obtained his driving licence and bought a Jaguar, which he only used to get around Wangi. Time magazine commissioned him to paint a portrait of Sir Robert Menzies for the cover of its issue of 4 April 1960, which contained a very long article describing to Americans 'the speed with which Australia is coming of age' under Menzies’s 'decade of unabashed wooing of free enterprise'. (The piece quoted a senior Australian diplomat who asserted 'Nowadays we can talk to anybody in the world without any sense of innate inferiority.') In 1965, Dobell was made OBE while MacMahon was made CBE. In 1966, however, MacMahon was visiting the artist at Wangi when an aide from Government House rang. Characteristically, Dobell had neglected to open a letter from the governor-general; MacMahon stood by as he rifled through a heap of intact correspondence, and tore open the envelope containing the offer of his knighthood. MacMahon said at Dobell’s memorial service that his friend was 'a remarkable man: soft, gentle, kind and considerate'. It was, perhaps, an unusual and brave tribute from one Australian man to another in 1970, especially in the punters' corner of the bar of the Wangi pub.

When Ted and Elizabeth MacMahon opened their Bennett Avenue home for the National Trust in May 1964, the guidesheet noted 'The drawing room is a particularly pleasing room, with its fine proportions, hand-made plaster ceiling with good cornice and centrepiece treatment, and its delicate and elegant colour scheme. One feels that William Dobell’s Archibald Prize-winning portrait of Dr MacMahon was painted especially for this room: notice the difference in colour tone used in the study for the portrait hanging nearby.' Whether or not Dobell kept the colour scheme of the MacMahons' study in mind as he worked on the final canvas, MacMahon was fortunate, in terms of his own posterity, to have had one of Australia’s great portraitists on his surgery list. In weighing up the suitability of a portrait for the collection, National Portrait Gallery curators, the director and board consider the interplay between the achievements of the sitter and the success of the portraitist, in conveying a sense of what the sitter was, or is, like to be around. Because MacMahon’s portrait is a brilliant one, his life’s work will become part of the Gallery’s broad fabric of stories. Many years after his death, his children’s generous donation initiates a new phase in the life history of the bold, benign surgeon whose image hung for decades on the walls of his historic homes.