Melbourne artist Darren McDonald strips portraiture almost entirely back to the abstracted shape of the sitter. In the National Portrait Gallery’s new collection guide

The Companion, Dr Sarah Engledow writes of Darren McDonald’s ‘characteristically gentle style.’ In a 2008 exhibition essay, Peter Fay identified ‘the distinctive McDonald eye, heart, mind.’ Reviews and catalogue essays for McDonald’s solo shows focus on the raw energy, tension and immediacy in his portraits. What is the nature of this style, eye, heart and mind that can gently suggest a sitter’s humanity and inner life with so few brushstrokes?

Meeting Darren McDonald for the first time in Sydney, we walked up to Juniper House to see the exhibition of finalists in the 2013 Doug Moran National Portrait Prize – McDonald’s portrait of ceramicist Stephen Benwell among them. On the walk, McDonald talked about his work: ‘I began to feel like getting friends into the studio – artists whose work I respect and who have been supportive.’ McDonald prefers to know his sitters, to ‘know them as artists’. McDonald didn’t start painting until his 30s. He completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Painting) degree from RMIT in 2000 and was awarded the RMIT’s John Storey Junior Memorial Scholarship.

McDonald paused as we passed some lawyers’ offices – he knew there were some works by Adam Cullen on their walls. McDonald has a strong sense of his vocation – ‘I have an artist’s life and I choose it’. His deep regard and enthusiasm for other artists’ work is striking and enlivening – he enjoys ‘being about and discussing art’. We stopped on the opposite side of the street to catch a distant glimpse of Cullen’s violent colour and line through the high office windows.

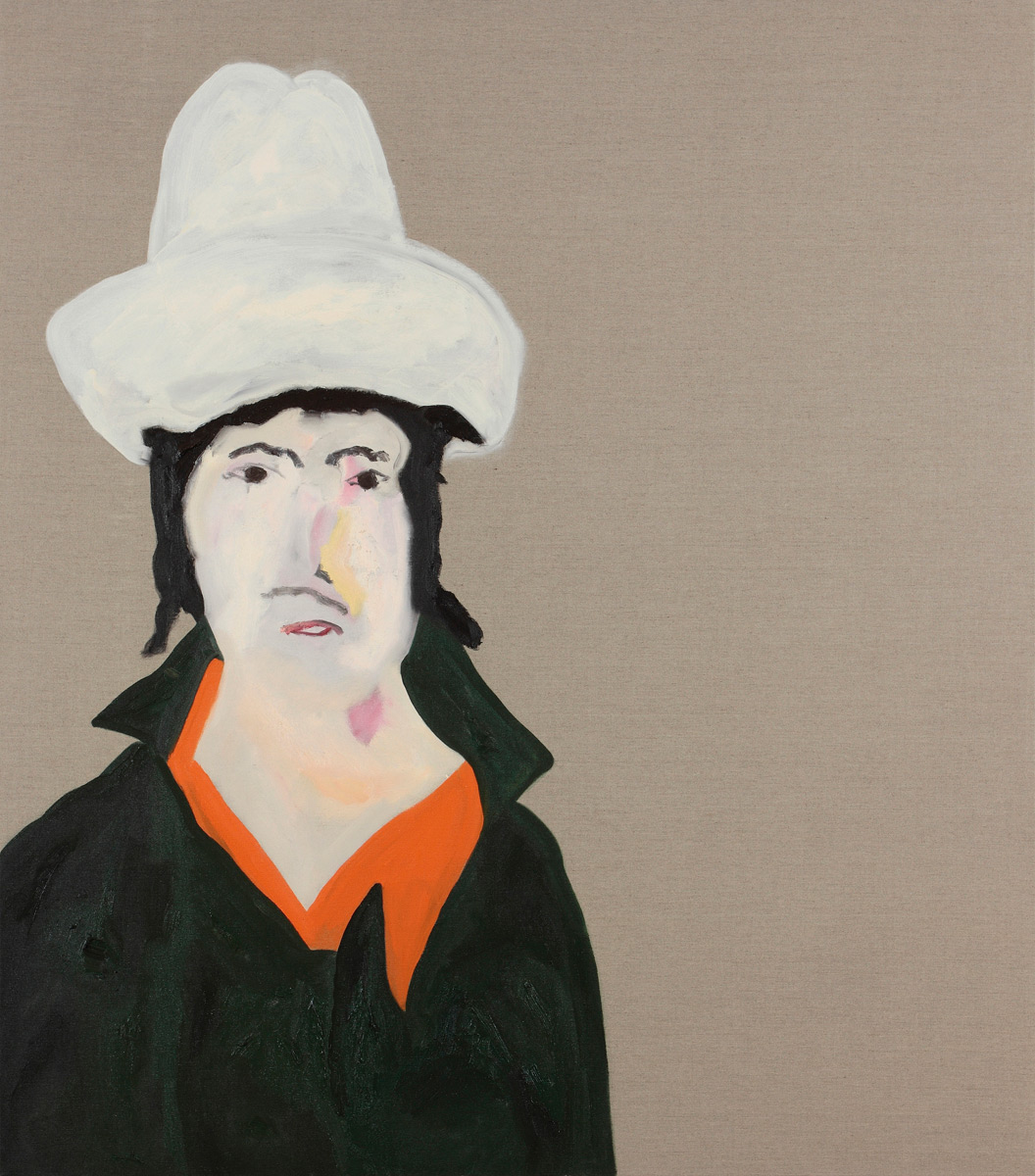

The Portrait Gallery purchased McDonald’s portrait of artist Adam Cullen in late 2012. It is highly unusual in the Collection in not having been taken from life. McDonald ‘met him a few times, then approached him through a friend to paint his portrait.’ The National Portrait Gallery holds Cullen’s portraits of director Neil Armfield and the Mordant family of arts philanthropists. Reviewing the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s major exhibition of Cullen’s work Let’s get lost (2009) in Art Monthly, Alan Dodge wrote of Cullen’s ‘catalogue of macabre, brutish and at times frightfully cheerful characters’ and Ashley Crawford wrote of Cullen’s ‘savage, visceral force’. Cullen was increasingly exhausted by serious mental and physical illness, and arranging a sitting was not possible, so in 2010 McDonald asked if Cullen would mind if he worked on a portrait painted from memory. He didn’t mind. Cullen died in winter 2012.

In painting Cullen’s portrait, McDonald used as his ‘sitter’ – by accident or by instinct – a photograph of American abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock that he happened to have in his studio. It makes sense: ‘I imagine they might have a few things in common. They both loved a drink and like a lot of artists were vulnerable in their art and life … Adam started working with the drip.’ Cullen’s figure is unsettled but not slumped or upright; he is balanced as if about to turn around. The sweeping brushstrokes belie its delicacy. The pinks and whites forming his ear and neck are almost a scar. McDonald models the face with tiny strokes of green at his cheeks and blue at the eye. It was Cullen’s gentleness that first struck McDonald, and this comes through clearly in the portrait. ‘Gentle’ is a word that recurs in our conversations.

Cullen and McDonald were two of many young artists noticed by Peter Fay – Sydney art collector, mentor, curator, artist, arts writer and, as McDonald put it, ‘a real patron’. Fay told me that he just collected work he liked and was interested in artists making good work. Fay’s advice to McDonald was ‘You are your own critic’. Talking about his work, McDonald is serious and frank. His practice and process are settled: ‘I would call myself a painter’ he says matter-of-factly. McDonald’s Self-portrait with Stetson and bright orange collar capture his own straightforwardness.

Standing in front of his portrait of Stephen Benwell at Juniper House on Oxford Street, McDonald says: ‘He came and sat for me, a gentle unique soul. He is living the life of an artist – the creative life. He will question you and he doesn’t suffer fools. There is always a discussion.’ ‘My sitters sit about a metre away’, McDonald explained, so Benwell ‘could see the painting being made through the linen.’ McDonald paints in oils direct to glue-sized Belgian linen and takes only an hour or so to complete a portrait.

McDonald’s is a fast, high-stakes process. ‘I work with a brush and if you make a mistake, you make it and it’s there’ McDonald calmly assures me. ‘There is a lot of room for error in my work due to it not having a background. Once the mark is made it cannot be removed’ he said in a 2014 interview for Artist Profile. When he is teaching, McDonald can’t stand students rubbing things out. He explained how he works: ‘Mostly I do an outline and then I fill it in. The outline takes the time and the filling in is very quick – the way a child would draw. There is very little walking away – it’s about looking.’

‘The first time someone sat for me was 2005 – that was Peter Fay – we did portraits together, sat for each other,’ he recalls. They worked in McDonald’s studio in Port Melbourne for five days. Fay slept on McDonald’s lounge room floor – ‘made of wood – no mattress, just a blanket and pillow’. This experience introduced portraiture into McDonald’s practice. They became friends and he recalls this time fondly. Before this marathon portrait painting session, ‘I was more interested in the animal – but that led to people – the eyes of both are important’. One of McDonald’s portraits of Fay still hangs in Fay’s study.

Visiting McDonald’s studio in Melbourne last June, I asked whether a ‘psychological edge’ – noted first by Peter Fay and often quoted in essays and reviews – is deliberately part of his style. In a 2005 essay, Ashley Crawford described this aspect of McDonald’s work as ‘a shattered distorted prism where the viscous nature of the paint and the inevitable instability of colour take on lives of their own’. Peter Fay cast it as a discontent with surface detail. ‘Nothing’s deliberate … it’s just the way it is,’ McDonald replied. An imposing budgerigar Mauve was on the easel behind me: modelled in waves of blue and yellow, McDonald depicts the big attitude and parrot-arrogance of this small bird. McDonald sees and represents the distinctive way each creature, human or animal, holds its body against gravity. His subjects appear momentarily paused in movement, despite complete balance. The ‘psychological edge’, energy, immediacy and tension in McDonald’s portraiture are bound up with his ability to represent an individual’s dynamic presence in the world.

One of the most influential art books published last century was Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye (1954) by Rudolf Arnheim, the first Professor of the Psychology of Art at Harvard. Arnheim noted how bodyweight is distributed asymmetrically in human figures, with each limb ‘unbalanced in itself’, balancing the whole in a manner unique to every person: ‘We identify an acquaintance at long distance by nothing more than the most elementary proportions or motions,’ he observed. A face, Arnheim writes, can be ‘grasped as an overall pattern of essential components.’ It is this subconsciously collected spatial data that McDonald is able to capture.

McDonald’s acutely observed portraits represent with disarming honesty how his sitters felt on the day. Hunched and leaning forward, Drasko Boljevic had been ill shortly before he came to sit for McDonald: ‘He was very drained.

So he ended up looking sad in the painting, even though I know him as such a happy person.’ ‘He has one of the best artist’s minds,’ says McDonald, and his empathy and affection shine through the finished work. ‘James Smeaton took it very seriously,’ McDonald recalled. In the portrait, Smeaton leans on his right foot, one hand in his pocket, the fingers of the other poking tensely straight out of his jacket, like columns. ‘He is very pale and that is difficult to paint – I think he ended up a little like a skeleton, but he liked the painting.’

McDonald’s portraits convey layers in perceiving another creature’s presence. In his interview with Artist Profile McDonald explained that he is ‘drawn to the plight of human nature, the hardships, how we survive this, and one’s instincts.’ There are parallels with the psychological and observational intensity of Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud or Jean Michel Basquiat. However, McDonald’s is a gentler revelation of his sitters’ characters, personalities and inner lives. He recognises that ‘it is difficult sitting for a portrait’ and his sensitivity to how a body is held in space means some of this inevitable discomfort transfers to the portrait, injecting a poignant humanity. His line and form are emphatic and lively with a quiet assurance, rather than

a frenzied exclamation.

McDonald focuses closely on his subjects: ‘I’m not interested in the background – I’m only interested in the subject.’ Energy flows from the negative space of the linen,

as it is drawn in to balance the figure. Arnheim wrote that ‘… Any line drawn on a sheet of paper … is like a rock thrown into a pond. It upsets repose, it mobilises space. Seeing is the perception of action.’ The space within the frame becomes an ‘interplay of directed tensions.’ This is why McDonald’s subjects do not float ghostlike against a Belgian linen sky. They stand firm on a ground against a horizon defined by their own balance and stability. This creates, as Peter Fay wrote in 2008, ‘a stillness … a moment when the subject is caught/trapped in its own vulnerability – its own private world.’

During our first conversation in November 2013, as we walked through Sydney, McDonald said he wanted to keep going with portraits of artists he knows, including painting his partner, the artist Robyn Astley. His portrait of Astley, Model, Painter with chair (2014) was shortlisted for the Benalla Nude Prize last year. He was also interested in exploring portraits of people with animals. His solo exhibition at Scott Livesey Galleries in Melbourne in February this year included several jockeys and their steeds, including some watercolours. His portrait Roy Higgins with Light Fingers warmly depicts a mutual understanding between creatures. McDonald’s practice in portraiture shows that an abstracted modernist revelation of a sitter’s inner life can be a gentle one. ‘This is what I want to do now,’ he told me.