Self portraiture within an artist’s oeuvre is generally attributed to three factors traceable to the early Renaissance: technical achievements in the manufacture of flat of mirrors; improvements in oil painting pigments and techniques; and the elevation through patronage in the status of artists from artisan to societal elite.

Today, self portraits are readily found amongst the submissions of Australia’s twenty-five or so annual portraiture prizes, exhibitions of which are hugely popular and draw significant audience participation.

In contrast, relatively few self portraits are found amongst the top echelon of Australia’s auction results. It’s another story in the international marketplace, however, where self portraits are esteemed and achieve staggering prices. While there are certain commonalities amongst the key points of attraction to potential buyers of self portraits in both arenas, most particularly the mystique of the auteur and the status of the artist in question, the disparity between the two markets is stark. A snapshot of select works from each sheds some light on this contrast and the influences that have informed and continue to characterise their difference.

Works by Francis Bacon and Andy Warhol account for eight out of the ten highest prices paid for self portraits in the international market, totalling a whopping $245 million dollars. The other artists in this tier are Vincent van Gogh and Edouard Manet. Viewed through the value prism of mystique, it is not surprising to find van Gogh topping the chart with a sale of US$65 million dollars for a rare unbearded self portrait. Van Gogh is the undeniable pinup boy for those seeking to fill the ‘self portrait as reflection of troubled artist’ niche in their collection (private and institutional). The artist painted around forty self portraits; only two have ever been offered at auction.

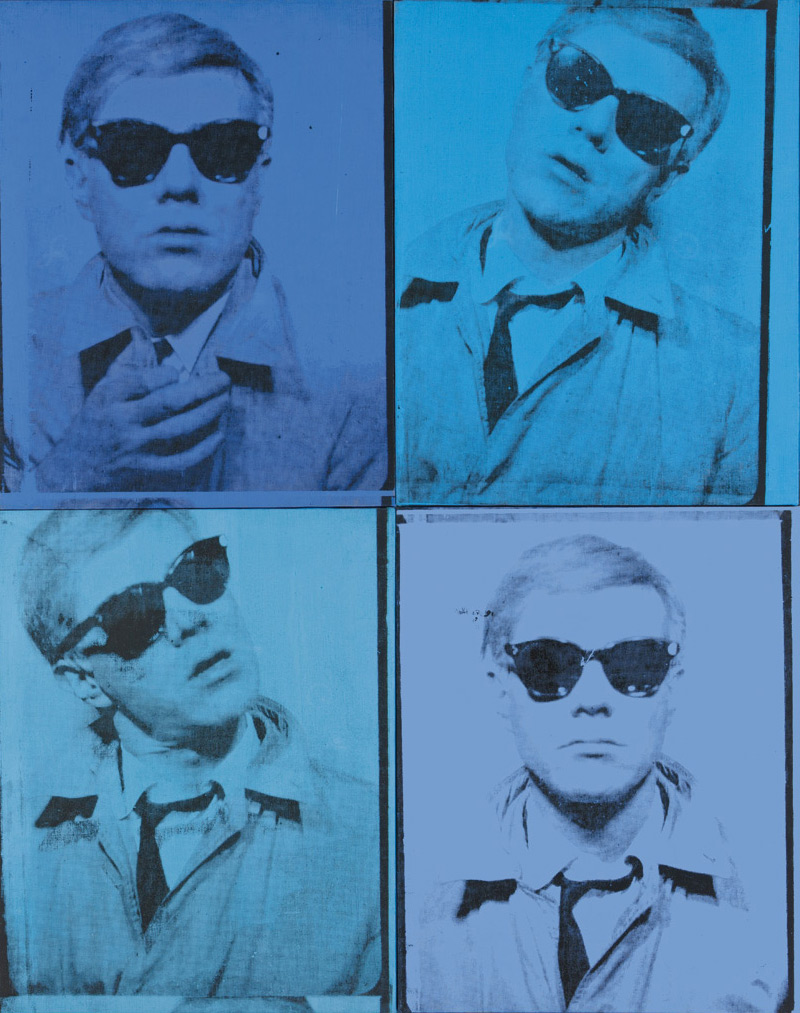

Warhol’s cachet as the ‘pope of pop’ also carries bad boy movie star glam and irresistible auteur mystique. Warhol overturned art practice and commodified the contemporary artist as cultural icon. The top prices paid for his self portraits occurred in 2011, when a European collector trumped rivals at US$34.25 million for the artist’s first Self Portrait, a work in four panels from 1964 showing Warhol wearing dark glasses and trench coat with the artist striking Fellini-like filmstar poses. The painting generated a bidding war that lasted sixteen minutes, reportedly the longest in auction history.

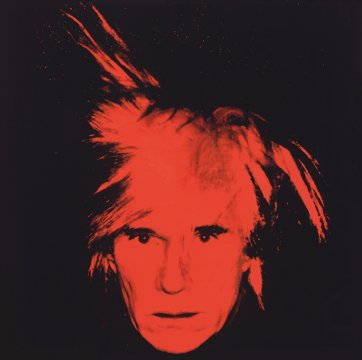

A red Self Portrait from the large scale ‘fright wig’ series of six, painted in multiple colours a year before his death in 1986, sold in the same auction for US$24.5 million. In 2010, fashion designer doyen and film director Tom Ford sold a similar self portrait in purple from another 1986 multiple series for US$29 million. Despite his complicit engagement with the media in exploiting his art, Warhol was very protective of his privacy. According to the auction PR, these final-year self portraits capture Warhol’s ‘attitude toward presenting his outer self, tempting us with the thought that he might finally let us glimpse his most intimate inner self’.

While Warhol’s decapitated floating head operates as an in-your-face graphic vanitas or memento mori motif, portraits by Francis Bacon, who critic John Berger coined the ‘prophet of a pitiless world’, offer a more penetrating insight to the human condition. In a 2004 review for the Guardian, Berger assessed his work thus: ‘He repeatedly painted the human body, or parts of the body, in discomfort or agony or want. Sometimes the pain involved looks as if it has been inflicted; more often it seems to originate from within, from the guts of the body itself, from the misfortune of being physical’.

Bacon’s portraits were predominantly of lovers, friends and acquaintances from the artistic and social milieu of London's Soho. Later in his career he painted the occasional high profile commission, including a triptych for Mick Jagger. His portraits are generally highly prized by the market, in particular those of Lucian Freud, but his self portraits are particularly potent and highly sought after. Bacon once commented that ‘old age is a desert because all one’s friends die’. It is not uncommon for artists to paint self portraits later in life. Bacon, who died in 1992 at the age of eightythree, had disingenuously stated in 1975 that his interest in self portraiture was a necessary result of his small inner circle, telling interviewer David Sylvester, ‘I loathe my own face, but I go on painting it because I haven't got any other people to do’.

It is well known that Bacon was a fan of Rembrandt self portraits in particular. A portrait photograph of Bacon taken in his studio in 1962 by Irving Penn shows a reproduction of Rembrandt’s Self Portrait with Beret 1659 from the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence on the wall. Bacon himself made much of this work, making pilgrimages to visit the painting in situ while living in France, and in the 1966 documentary Sunday Night Francis Bacon, he acknowledged his reverence for the ‘tightrope walk’ between the abstract and figurative at play in the Rembrandt work.

From the early 1960s Bacon’s portraits were regularly painted as triptychs, which enabled the artist to depict an individual in three aspects, a practice he likened to police mug shots. The triptych also references the drama of painted altar pieces and the multiple squared strips of photographs produced in automated photo booths, which Bacon used for candid self portraits. This highbrow/lowbrow dichotomy is an accurate reflection of the artist’s sources, which stem from the work of European masters Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Ingres, Degas, Van Gogh, Picasso and Velázquez, to contemporary ephemera such as photographs, magazine cuttings and newspapers. Bacon, who has been described variously as a cannibal and magpie, also mined other nineteenthcentury socio-historical primary material including the sequential photographs of Eadweard Muybridge’s figures in motion from Animal Locomotion 1887 and photographs of male patients in convulsion.

Writing for a 2005 exhibition of his portraits and heads at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Richard Calvocoressi noted that Bacon regularly quoted Muybridge’s visual lexicon, especially the ‘chance pose or fluid movement [that] led Bacon to develop portraits of a fleeting glance or nuance of expression’. Bacon used this device to great effect on himself in Three Studies for Self Portrait, 1975, which sold for US$30.73 million in 2008. In the triptych format, features are smeared and sliced across three canvases. The end result is a portrait that appears to resemble a series of stop-motion film stills that regurgitate some darker element of the psyche/soul, akin to the canvas in the Picture of Dorian Gray. Bacon wanted his pictures ‘to look as if a human being had passed between them … leaving a trail of the human presence’. The majority of Bacon’s self portraits remain in private hands, which is not surprising as few institutions can compete with prices around the $30 million dollar mark. In 2007, the artist Damien Hirst, reportedly the richest artist in the world, outbid diamond traders and hedge fund managers to secure his fourth work by Bacon, a foot-square Self Portrait from 1969 for US$29 million.

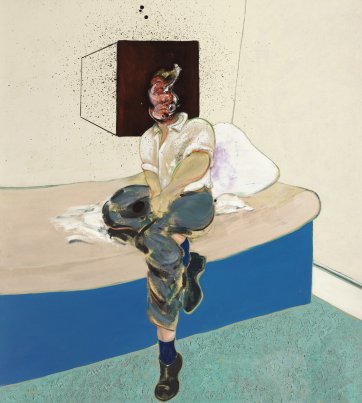

The most expensive self portrait by Bacon is a full-length work – one of only twelve known to exist – which sold in 2007 for $38.3 million. This year, Bacon’s full-length Study for Self Portrait 1964 became the fourth most expensive self portrait ever sold, reaching just shy of $33.6 million dollars in June. The catalogue notes reveal that Bacon had placed his head on the body of his lifelong friend Lucian Freud, painted from a recently discovered photograph by John Deakin. When Study for Self Portrait was first offered at the height of the global financial crisis in 2008, the work did not draw a bid. Freud died in 2011, and the additional hype in light of this information no doubt contributed to this exceptional result.

Study for Self Portrait 1964 depicts Bacon seated on a bed, his head in havoc, against a seemingly blood splattered cage/box. The Art Gallery of New South Wales has another full length portrait study that depicts the artist in the same cross-legged pose as the Lucian Freud/ Bacon figure, on a chair within a cage in the fashion of his early portraits of popes and others, and with the head defined by a similar dense black box. Both works are strong examples of the artist’s interest in literal self-effacement. In the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ major Bacon show that opened in mid- November, heads, portraits and self portraits number nineteen amongst the fifty-four works on display.

Manet’s depiction of himself with artist palette aside, the top ten self portraits on the international market offer penetrating meditations on the human condition. In stark contrast, the Australian top ten is dominated by whimsy, irony – and landscapes. As with the international market, the list comprises a few artists who dominate the ‘most traded’ and/or ‘blue-chip’ industry profiles: John Olsen, William Robinson, John Brack, Jeffrey Smart and William Dobell.

Smart, Heysen and Lambert secured spots with traditional depictions. Heysen’s is akin to Manet’s – a strong self affirmation featuring typical painting accoutrements. Lambert doesn’t need a painter’s paraphernalia to denote success. His standing was secure by the 1920s and the portrait shows him in a virile pose, replete with smoking jacket, pipe and waxed moustache with gladioli, a symbol for victory. The work is now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, a gift of John Schaeffer ao in 2003. In contrast, Dobell depicts himself in a rather dishevelled close up with his dog, the image swirling with the white over-painting of his late works, also readable as smoke drifts from the cigarette dangling from his mouth. Four of the top ten Australian works are ostensibly landscapes, for which the Australian art market has an enduring love affair. Founded on the doctrine of terra nullius, this country’s settler society and cultural psyche was built by conquering frontiers and dominating the landscape and its peoples. The art market is heavily influenced by this debt; the top price paid this year to date is $2.52 million for a colonial settler painting by Arthur Streeton.

The domination of the fine art market by landscapes is unremarkable, but landscape dominating an artist’s self portrait is highly peculiar. In view of the canon of western art historical tradition, to some, no doubt, it would be deemed perverse. Indigenous artists would largely disagree, and for many it is a natural assumption. This was tested in 2006 when Yulparija artist Weaver Jack entered an abstract depiction of country in the Archibald Prize for portraiture, its acceptance causing considerable controversy. Landscape influences and nourishes individual identity and self-regard worldwide, and not just for Indigenous peoples. William Robinson is a painter and a farmer, and his self portraits reflect an intimate engagement with the landscape of his domicile that operates on multiple levels. The whimsy and charm of inserting himself far off centre-stage in his landscapes speaks volumes about his self-regard – his view of himself in the bigger-picture of man versus nature, as well as his place in the art world establishment. Landscape with Sunset and Self Portrait holds the current record price for the artist’s work at $696,000, while Landscape and Self Portrait, circa 1987 sits in the top ten at $306,000.

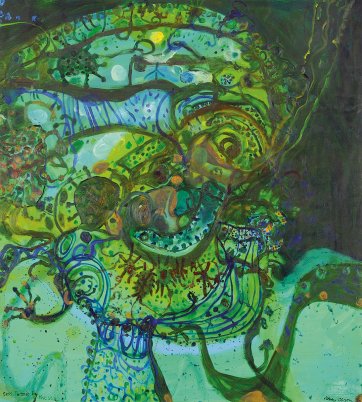

There is no ‘tightrope walk’ between the abstract and figurative in John Olsen’s Self Portrait by the Sea, which sold for $150,000 in June 2010 and sits sixth in the Australian top ten. His identity as one of Australia’s formative landscape artists and Sydneysider is made apparent by the painted sinuous line that is unmistakably Olsen. The artist’s central casting and prominent figuration in Afternoon walk, Dunmoochin are more easily read in terms of traditional portraiture.

John Brack’s Self Portrait from 1955 is a wry example of proclaiming artistic intent through self portraiture. Brack has been christened the ‘master of urban irony’, and in this intimate but sterile space he gazes through the imagined mirror to meet us, the subjects of his painterly enquiries. This striking work was repatriated from America in 2000 as part of the dispersal of the Mertz Collection from the University of Austin, Texas and claims the second highest price for a self portrait at auction. It is fortunate for our cultural patrimony that the market here is a few zeros off international pace. The National Gallery of Victoria was able to acquire the work with the assistance of the Gallery’s Women's Association for $442,500.

Brack’s oeuvre, which is predominantly figurative, regularly features in the top ten at auction and he holds four of the top ten prices of all time, totalling $10.68 million. Jeffrey Smart is another blue chip artist. Like Brack, his Self Portrait also places him front and centre, situated against a hoarding. Like Brack, he is contextualised by the identifiable iconography of his oeuvre and bears the deadpan expression he gives the players in his paintings. Like Lambert, his attire, in this case open neck shirt and cravat, speaks volumes about his sense of self. The work is now in the collection of the University of Queensland.

Portraits are important reminders of our humanity, and self portraits offer artists the chance to move beyond likeness to push the boundaries of enquiry further. As the critic John Russell points out, Bacon’s heads are about ‘the disintegration of the social being that takes place when one is alone in a room’. Perhaps it’s the relative youthfulness of our nation that compels us to constantly contextualise our place in the world, or perhaps it’s the Antipodean light, but it seems that the Australian art market is not as predisposed to works of introspection as those in northern climes. We are fortunate that Australian public institutions continue to embrace the intrigue of the inner self.